Template Learning: Deep learning with domain randomization for particle picking in cryo-electron tomography – Nature Communications

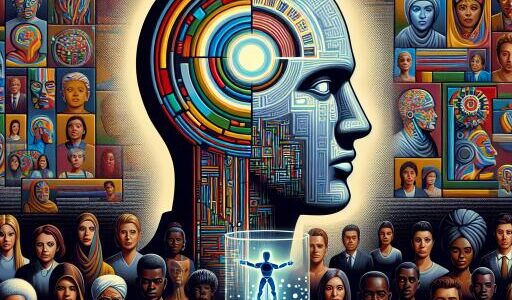

Deep learning has transformed particle picking in cryo-electron tomography (cryo-ET), but it still hinges on large, painstakingly curated training sets. A new approach called Template Learning flips that dependency: it trains models entirely on physics-based simulations enriched with domain randomization, then deploys them directly on real data—often matching or beating methods trained on manual annotations.

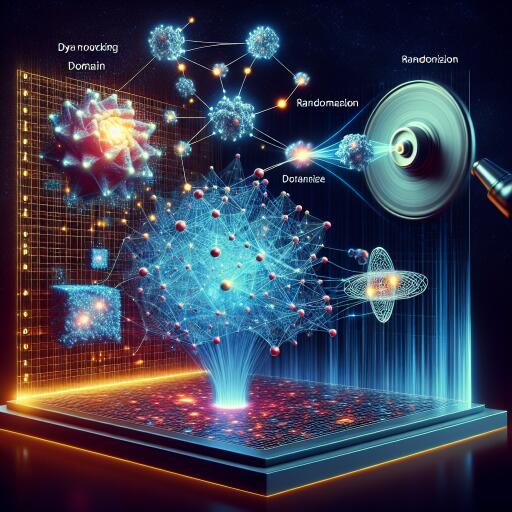

How Template Learning works

- Start from templates: Use one or more atomic structures (or lower-resolution volumes) of the target biomolecule.

- Model structural variability: Generate flexible variants via Normal Mode Analysis (NMA) to reflect compositional and conformational differences.

- Add distractors: Place a large library of unrelated protein assemblies to mimic real cellular clutter and reduce false positives (inspired by TomoTwin).

- Pack densely with the Tetris algorithm: A fast, general placement scheme that iteratively drops molecules at random orientations as close as allowed to neighbors, achieving realistic crowding without expensive simulation.

- Simulate physics with Parakeet (MULTEM backend): Render tilt series with a carefully chosen set of randomized parameters.

- Reconstruct and train: Reconstruct tomograms (e.g., weighted back-projection), then train a segmentation-based model (DeepFinder) on volumes and ground-truth coordinates.

- Deploy on real data: Predict segmentations, cluster with MeanShift to get particle coordinates and sizes, and optionally apply masks to suppress unlikely regions.

Domain randomization that matters

Template Learning embraces diversity over perfect realism. Instead of attempting to capture every imaging nuance, it randomizes a small set of high-impact parameters: electron dose (SNR and beam damage), defocus (CTF), tilt range, tilt step, and ice density (thickness/solvent variation). With three defocus values and two choices for each of the others, 48 combinations proved sufficient to train robust models without exploding the simulation space.

Crowding solved: the “Tetris algorithm”

Existing random-placement approaches either leave unrealistic voids or demand heavy computation (e.g., molecular dynamics) to reach high packing densities. The Tetris algorithm offers a pragmatic middle ground: at each iteration, place the next molecule at a random orientation as close as possible to previously placed molecules, given a user-defined minimum distance. The result is fast, high-density packing for arbitrary shapes—critical for training models to cope with overlap, missing wedge artifacts, and occlusions in real tomograms.

Benchmarking on ribosomes: simulations vs. the real world

Using six ribosome templates with NMA-generated variants and a diverse distractor set, the team simulated 48 tilt series with Parakeet, reconstructed them to match the sampling of the EMPIAR-10988 dataset, and trained DeepFinder on ~6,500 synthetic ribosomes. When applied directly to 10 in situ tomograms (VPP, no preprocessing), the simulation-trained model produced segmentation maps that, after MeanShift clustering, achieved a median F-score of 0.85—surpassing template matching and previous deep learning models trained only on experimental data (prior best around 0.83), and importantly, evaluated across the full dataset rather than a subset.

This is notable because earlier methods (DeepFinder, DeePiCt) were trained on thousands of manually annotated ribosomes from 8 tomograms and tested on 2; in contrast, Template Learning required no experimental labels and generalized across all 10.

What really moves the needle (ablations)

- Multiple templates + flexible variants: Both boost recall and precision; NMA can partially offset the lack of multiple PDBs.

- Diverse distractors: Essential for high precision; limiting distractor variety spikes false positives.

- Realistic crowding: Higher densities via Tetris materially improve F-scores; sparse simulations underperform.

- Low-res volumes: Converting maps to pseudoatomic models enables training when atomic structures are unavailable—some precision loss but usable recall.

- Cross-domain robustness: Models trained with VPP/DEF variability handle domain shifts better than prior approaches.

Challenging target: Fatty Acid Synthase (FAS)

FAS is notoriously hard to pick due to its shell-like architecture and lower SNR. With two FAS templates and NMA-generated variants, the simulation-trained DeepFinder model outperformed purely supervised models on VPP data and achieved up to 22% F-score on DEF data—an improvement over reports where DEF picking failed.

Then came fine-tuning: starting from the simulation-pretrained model, adding only ~150 annotated FAS particles from two VPP tomograms (carefully avoiding overfitting) delivered a large F-score jump. Scaling to ~600 annotations across eight tomograms improved further and surpassed previous supervised methods trained solely on real labels. The takeaway: simulation pretraining drastically reduces the labeled data needed, contradicting the notion that fewer than ~600 particles are insufficient for effective training.

Real-world test drive: nucleosomes in new data

To evaluate zero-shot utility on a new, unlabeled dataset of partially decondensed mitotic chromosomes, the team used six nucleosome templates with NMA variants and tuned the pipeline for smaller targets: a higher template-to-distractor ratio, larger training volumes (faster physics simulation per particle), and 8 Å pixel size to match the experiment.

After inference and MeanShift clustering (radius ~ nucleosome size), they obtained ~18k picks and performed reference-free subtomogram averaging (Relion 4.0), reaching 12.8 Å resolution with isotropic angular coverage—no heavy curation needed.

In contrast, template matching (PyTom) produced obvious false positives (e.g., gold and Percoll particles) and a pronounced orientation bias towards side views—a known missing-wedge artifact for cylindrical shapes—requiring aggressive filtering. Only ~57% of top-scoring picks resembled nucleosomes after classification. While averaging ultimately achieved a comparable 12.9 Å resolution, it did so with more manual intervention and a biased orientation distribution. Template Learning avoided both pitfalls.

Why this matters

Template Learning shows that robust particle picking can start from prior structural knowledge plus well-designed simulations—no large annotated set required. Physics-based rendering, realistic crowding, and focused domain randomization make models resilient to real-world variability. And when ground truth exists, light fine-tuning (hundreds, not thousands, of particles) often suffices to reach or surpass fully supervised baselines.

For labs facing hard-to-annotate targets, scarce labels, or cross-instrument variability (VPP vs. DEF), this template-first strategy offers a practical, time-saving alternative: simulate broadly, train once, deploy anywhere—and fine-tune only if you must.