AGI debate heats up as Demis Hassabis calls Yann LeCun’s view ‘plain incorrect’

The long-running debate over what counts as “general” in artificial intelligence flared again after Google DeepMind CEO Demis Hassabis said Meta’s Yann LeCun was “plain incorrect” about the nature of human and machine intelligence. The exchange highlights a fundamental rift over how to reach artificial general intelligence (AGI) and what “general” even means.

Is human intelligence general or specialized?

LeCun, Meta’s chief AI scientist and a Turing Award recipient, argues that human intelligence isn’t truly general. In his view, people excel at navigating the messy, social, real world but falter at highly structured, formal tasks. He uses chess as an example: we can learn it and play well, but we’re not systematically optimal reasoners in such domains, and our competence reflects evolved specializations rather than universal generality.

Hassabis countered that this framing mixes up two different notions: “general” versus “universal.” He maintains the brain is extraordinarily general—capable of learning an immense range of skills across domains—without claiming it’s universally optimal at everything. The fact that humans conceived of chess, airplanes, and modern science, he argues, is itself strong evidence of generality, even if human decision-making is bounded by time and memory.

The No Free Lunch theorem—and why it doesn’t settle the question

Hassabis acknowledged the No Free Lunch (NFL) theorem, which states that no single learning algorithm is best for all possible problems. In practice, any useful system is biased toward the kinds of tasks and data it faces. But he argues this doesn’t negate generality—it simply recognizes practical limits.

- No Free Lunch (in ML): There is no universally best algorithm across all conceivable tasks. Performance depends on the match between the algorithm’s inductive biases and the task distribution.

- Implication for AGI: A generally capable system will still embody priors and structures suited to our world, not every possible world.

Turing Machines, brains, and the scope of “learnable”

To frame “generality,” Hassabis pointed to the Turing Machine lens: a sufficiently flexible architecture can, in principle, learn any computable function given enough time, data, and memory. He characterizes both human brains and today’s AI foundation models as approximate Turing Machines—resource-bounded but broadly capable. Under this view, humans being imperfect at chess doesn’t undermine generality; it reflects finite resources and training, not a lack of general learning machinery.

Clashing roadmaps to AGI

Beyond definitions, LeCun and Hassabis diverge on engineering paths to AGI:

- Hassabis: Scaling today’s large language models (LLMs) is not sufficient on its own; at least one or two major breakthroughs are still required. He has long emphasized integrating richer reasoning, planning, and grounding with continued scaling.

- LeCun: LLMs are a dead end for AGI because they lack robust continual learning and grounded understanding. He champions “world models”—internal representations that capture physics, causality, and temporal dynamics—as the core of advanced machine intelligence. He also prefers the term “Advanced Machine Intelligence” over “AGI.”

The chess flashpoint

LeCun’s chess example has become a focal point because it distills the dispute. If humans were truly “general,” shouldn’t we be flawless at a precise, closed-world game? Hassabis contends that’s the wrong yardstick: generality is about the ability to acquire a vast range of skills across domains, not omniscience in a narrow one. The fact that a human like Magnus Carlsen can reach superlative skill in chess, despite biological constraints and an evolutionary history aimed at survival rather than symbolic board games, underscores how far general learning can go.

Why this matters

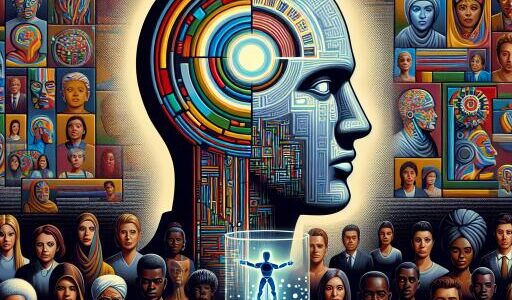

Words shape roadmaps. If intelligence is “super-specialized,” research may focus on many narrow modules stitched together. If it’s “extremely general,” the priority shifts to architectures that can learn, plan, and adapt across tasks with minimal hand-engineering. Funding, benchmarks, and safety planning all hinge on which definition carries the day.

In practical terms, both camps are converging on a similar frontier: AI systems that combine data-driven learning with grounded models of the world, longer-horizon reasoning, and efficient memory. Whether that future is realized by scaling current foundation models plus new modules, or by a qualitatively different world-model-first architecture, remains the core bet.

The bottom line

LeCun is pushing the field to avoid complacency about LLMs and to build systems that understand and predict the real world. Hassabis is pressing for a precise definition of “general,” arguing that human cognition demonstrates remarkable breadth even if it’s resource-bounded and specialized in places. The disagreement is substantive—but it also reflects a healthy tension driving AI toward deeper theories and more capable systems.