Communities of plasmids as strategies for antimicrobial resistance gene survival in wastewater treatment plant effluent – npj Antimicrobials and Resistance

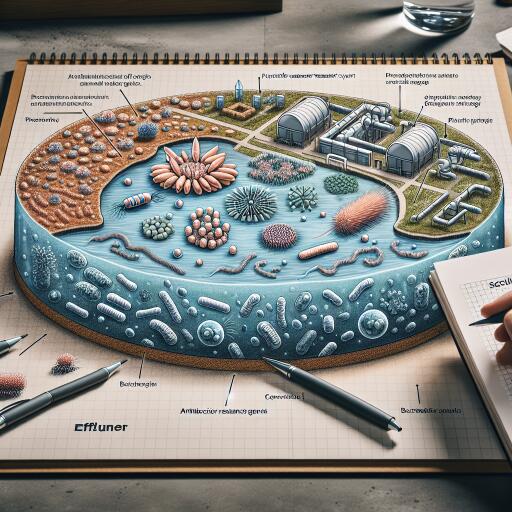

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) doesn’t just spread through individual genes—it often moves in packs. A new study of plasmids recovered from wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) effluent shows that groups of plasmids frequently co-exist inside the same Escherichia coli cell, forming “plasmid communities” that collectively carry and mobilize resistance, virulence, and metal tolerance genes. This community behavior may be a key survival strategy that helps AMR persist and spread across environments and hosts.

What the researchers did

The team captured, circularized, and fully resolved 173 plasmids from E. coli isolated from WWTP effluent previously profiled for antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs). They annotated each plasmid for ARGs, metal resistance genes, virulence factors, mobility elements, and replicon types, and compared them with the global PLSDB plasmid database to understand how these plasmids relate to those found in human, animal, and environmental samples.

Key findings at a glance

- Scale and structure: Plasmids ranged from 2,337 bp to 292,404 bp; “mega-plasmids” over 100 kb made up 36% of the set. Most E. coli carried multiple plasmids; single-plasmid occupancy was rare.

- AMR load: 42% of plasmids carried at least one ARG, spanning 33 unique genes across 10 drug classes (including aminoglycosides, beta-lactams, quinolones/fluoroquinolones, macrolides, polymyxins, and tetracyclines). No carbapenemase genes were found. Among AMR plasmids, 73% were multidrug-resistant, with up to 12 ARGs each.

- Mobility: ARG-bearing plasmids were predominantly conjugative. A few small plasmids were mobilizable or non-mobilizable.

- Co-selection and co-dependence: AMR and non-AMR plasmids were often co-transferred, and some non-AMR plasmids relied on AMR plasmids for selection or mobilization.

- Metal and virulence: Distinct non-AMR plasmid groups carried mercury resistance operons or iron acquisition systems (sitABC) and virulence islands (e.g., iroBCDEN, iucABCD, iutA), indicating non-antibiotic pressures may help maintain plasmid communities.

- Toxin–antitoxin systems: 32 distinct TAS genes were detected, distributed across sizes; even some small, non-AMR plasmids carried complete TAS, likely enhancing plasmid persistence.

- Environmental linkage: Clustering against PLSDB showed strongest similarity to E. coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae plasmids and to sources like bovine feces, pigs, ground turkey, and human stool/urine—less so to soil, water, and general sewage.

Communities of plasmids: who co-exists with whom

The study’s core insight is community-level organization: specific sets of plasmids repeatedly co-occurred within the same E. coli host, often mixing conjugative mega-plasmids with smaller satellites.

- Four-way mega-plasmid communities: 224 kb (IncH1/H2/RepA), 139 kb (IncFIB/FIC), 102 kb (IncFII), and 96 kb (IncFII/IncI1) frequently co-existed. ARG content overlapped minimally, suggesting complementary functions. Despite selecting colonies on tetracycline, some co-existing plasmids lacked tetracycline resistance and persisted via the community’s shared selection.

- Paired mega-plasmids:

- 287/292 kb (IncHI2A/IncH2B/RepA) + 140 kb (IncFII): the larger plasmids carried extensive ARG and metal resistance repertoires; the 140 kb partner lacked ARGs but had mercury resistance. Small 5.5–6.3 kb plasmids sometimes joined these communities.

- 178 kb (IncIA/C2) + 117 kb (no replicon assigned): selected via beta-lactam resistance; the 178 kb plasmid also carried qacE (biocide resistance). Often accompanied by a unique 5.5 kb plasmid.

- Mid-size clusters: 34, 55, and 56 kb plasmids frequently co-occurred with multiple small plasmids. Notably, isolates rarely carried only small plasmids, even when a small plasmid encoded the selectable resistance.

- Singletons and exclusions: Some conjugative mega-plasmids (e.g., 114 kb, 144 kb) tended to appear without small plasmids. In communities containing a 96 kb plasmid, small plasmids were absent—hinting at incompatibility, ecological exclusion, or resource competition.

What wasn’t found—and why

Cross-checks with prior qPCR arrays on the same samples showed strong agreement: plasmid-borne ARGs largely matched qPCR detections. Genes typically chromosomal (for example, certain efflux pumps like mexB) or associated with Gram-positive hosts (e.g., vanB) were absent from these plasmids—likely because E. coli was the capture host. Interestingly, qnrB and tetB appeared on plasmids here but were missed by the earlier qPCR assay, underscoring the value of direct plasmid sequencing.

Genetic plasticity: same but different

Even within highly similar plasmid groups, the genomes were not static. The team observed rich structural variation—from reshuffling and inversions in small Col-type plasmids to large insertions/deletions in mega-plasmids associated with insertion sequences and transposons.

- IncI signature shufflon: A cluster of ~96–97 kb plasmids (IncI/IncFII) showed all rearrangements confined to the shufflon region, which diversifies the PilV adhesin for conjugation partner specificity.

- Origin-of-replication hotspots: Several IncP plasmids shared tandem duplications or collapsed repeats localized to the replication origin, with otherwise stable backbones.

- Large-scale edits in IncH: Related 224 kb vs 287/292 kb plasmids differed by tens of kilobases across scattered loci, adding or dropping ARGs (e.g., sul1, qnrA) and regulatory/metal-associated genes—evidence of modular, IS-driven remodeling.

Why this matters

WWTP effluent is a busy interchange for genetic cargo. This work suggests that resistance doesn’t rely solely on a single “super plasmid” but often on an ensemble: plasmids that collectively bring mobility, selection advantages (antibiotics, metals, heat tolerance), virulence, and persistence mechanisms (toxin–antitoxin). Such communities can keep non-resistant plasmids in circulation and help complex traits survive environmental transitions and host jumps.

Caveats

- Host bias: Using E. coli as the capture host likely underrepresents plasmids adapted to Gram-positive bacteria or to non-enteric species.

- Selection bias: Antibiotic selection (e.g., tetracycline, ampicillin) favored communities containing the corresponding ARGs, potentially missing other plasmid constellations.

The big picture

By shifting focus from single plasmids to plasmid communities, this study reframes how we think about AMR persistence and spread. In WWTP effluent—where bacteria, antibiotics, metals, and other stressors mix—ensembles of plasmids form adaptable, modular systems that can persist even when some members lack obvious advantages. Monitoring these communities, not just individual genes, may be crucial for anticipating AMR trajectories and designing interventions that disrupt the ecological alliances enabling resistance to thrive.